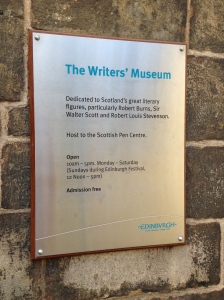

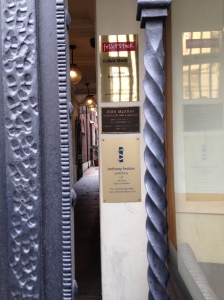

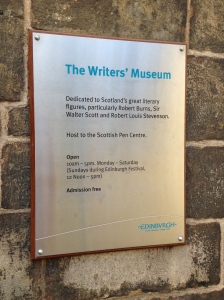

Before I set out to find the Writers’ Museum, I had passed by it several times, never knowing it was there. When I looked up its location on a map, I had a moment of worry that this museum dedicated to Scottish writers – in particular to Robert Burns, Sir Walter Scott, and Robert Louis Stevenson – was like Diagon Alley and completely hidden to Muggles (non-authorial legends, in this case?). As it turns out, I needn’t have worried, because once I knew where to look, I quickly found a tiny passageway that opened into a stone courtyard dominated by a stone house at one corner, a turret rising in elegant arching lines over the door.

The house is called Lady Stair’s House after a famous owner during the 1700s, but it was built in 1622. Information on the house, its history, and its restoration is found on the first floor.

Upon entering the building, I was met immediately with a winding staircase, headed upstairs on the left and downstairs on the right, and a door leading into the main floor. A sign indicating the downward stairs pointed the way to the Robert Louis Stevenson collection. As RLS is the general subject of my research paper, I headed for his collection first. The display was organised chronologically, moving from RLS’s birth onward through his life toward his death. The first room included photographs, paintings, and other relics from his early life, ending with the pivotal event of meeting Fanny Vandegrift Osbourne, the married woman who would later become Stevenson’s wife. The second room continued the chronological arrangement, moving on to cover his later life.

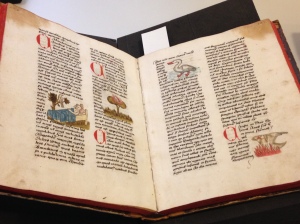

This collection included both original materials and reproductions of photographs and paintings housed elsewhere, as well as items belonging to Stevenson. Some of the most remarkable of these items are a dresser belonging to the Stevensons which was made by the infamous Deacon Brodie, Stevenson’s riding boots and whip, and his fishing rod.

One of the most notable aspects of the Robert Louis Stevenson collection at the Writers’ Museum was not part of the collection at all, but rather the friendly and helpful gentleman who was working there, welcoming visitors, taking note of where they come from (while I was in the museum, I heard notes of Tennessee, France, and Honduras – clearly RLS has a great deal of international appeal), and giving visitors information about how the collection is arranged, about Stevenson and his life and works, and about specific items in the collection. This knowledgeable gentleman, as it turned out, has studied Stevenson extensively in collections and museums all over the world, and is in fact in the process of transcribing an unpublished manuscript by RLS. When I told him that I was writing a paper on RLS, but that I wasn’t sure what my topic would be yet, he was able to tell me what subjects had and had not been covered, and where I could find pertinent resources. It seemed he had utilized just about every RLS collection in existence! I was very lucky to meet him in the course of my research!

After my exploration of the Stevenson collection, I headed upstairs to the upper floor, which had a display of photographs of Scottish writers outside of the great trio that was the main focus of the museum. There was another display dedicated to forgotten female writers, and information on Lady Stair’s House. The main floor contained the Robert Burns and Sir Walter Scott collections, which included mostly paintings and letters, and a few personal affects and some furniture belonging to the authors. This floor also included a small shop selling books by Scottish authors.

In the courtyard outside of the museum were paving stones engraved with quotations by Scottish authors – a nice touch to lead the way to this charming museum.